"I have seen the things which were brought to the King from the new

golden land . . . a sun all of gold . . . and a moon all of silver . . .

wondrous weapons . . . strange clothing , , , and all manner of

marvellous things for many uses . . . in all the days of my life I have

seen nothing that so rejoiced my heart as these things, for I saw among

them wonderful works of art, and I marvelled at the subtle genius of men

in distant lands"

"I have seen the things which were brought to the King from the new

golden land . . . a sun all of gold . . . and a moon all of silver . . .

wondrous weapons . . . strange clothing , , , and all manner of

marvellous things for many uses . . . in all the days of my life I have

seen nothing that so rejoiced my heart as these things, for I saw among

them wonderful works of art, and I marvelled at the subtle genius of men

in distant lands"

These words were written in 1520 by the great German artist, Albrecht Dürer. The "new golden land" was Mexico; the wonders of which he wrote were given by Aztec emperor Moctezuma to Hernan Cortés and sent to the King of Spain.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo marched with Cortes and. in his True History of the Discovery and Conquest of New Spain, he tried to describe the wonders of the great market near Tenochtitlan as he saw it 1519. His list of marvelous goods runs on for pages and pages.

Mexico, and especially Oaxaca, still has the ability to inspire awe in its visitors through the enduring traditions of native arts and craftsmanship and the vibrant creativity of its people. Your visit is an opportunity to get some neat stuff and that is the premise of this issue. So let's go shopping! -- Warren Sharpe

|

|

The best Oaxacan hammocks are made in Juchitán and Mitla, but you don't need to leave Puerto Escondido to buy a good quality hammock at a good price. In fact you don't even have to leave the beach. Sooner or later you will be approached by one of the colorfully garbed ladies from Juchitan de Zarragoza calling out: "¿Hamacas, amigo?"

Juchitan is a vibrant center of the Zapotec culture of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, where hammocks are a way of life and their manufacture on small, traditional looms are an important cottage industry.

The women street vendors from Juchitan - - Angela, Dona and Cristina are the best known - are easily recognized by their richly embroidered blouses and long, colorful skirts, the traditional costume of the matrilineal Tehuanas. The bundles of hammocks that they balance on their heads can weigh as much as 20 kilos.

A hammock should last for many years, if you know what to look for in terms of material, size and quality. The most popular materials used nowadays are silk, cotton and nylon. The brightest colored ones are generally nylon, while cotton and silk hammocks are either undyed or else tend to be in more natural tones.

There are four sizes to choose from, the size calculated according to the number of pairs of string at each end. The smallest and therefore the cheapest is the sencillo (single), which is woven across approximately 50 pairs of string. Next is the doble (double) with 100, matrimonial (marriage-size) with 150 and matrimonial especial or family size, which should have at least 175 pairs of string at each end. A good family sized hammock can weigh up to 4 kilos, with as many as 300 pairs of string at each end!

While it might only take a day to make the simplest sencillo hammock, it can take 15 days or even a month for artisans to weave larger hammocks. The strongest hammocks are obviously those with the most strings to support them, and of course, you.

However, feeling comfortable is what is most important when choosing your hammock. It should be comfortable enough for you to fall asleep in. Prices for these Zapotecan art works range from US$15 to US$300. When you buy a hammock from one of the street vendors, you are helping to sustain an important, fiercely independent indigenous culture.

They are easily identified by the gingham aprons worn by the women. These aprons (mandiles), worn over multi-pleated, satin dresses, have been adopted as a modern expression of their cultural identity.

Their home is in Tierra Caliente, the hot valley lands of the upper Balsas River. They still speak Nahuatl, the language introduced into the region by the Aztecs in about 1300 AD.

Their crafts are handed down father to son and mother to daughter,

carrying on a creative tradition that reaches back to the craftsmen who

produced the exquisite carved jade and ceramic figurines of prehispanic

times.

Their crafts are handed down father to son and mother to daughter,

carrying on a creative tradition that reaches back to the craftsmen who

produced the exquisite carved jade and ceramic figurines of prehispanic

times.

The apron ladies on Puerto's Adoquín pedestrian mall hand paint and sell those inexpensive blue ceramic souvenirs; ash trays, vases, plates and cups, lighter holders and pens. They also make bracelets and necklaces, keyrings and other doohickeys from shells and beads. While the initial response to these displays of cheap trinkets is to reject them as shlock, if you look carefully you can discern the work of those artisans who really take pride in their work and try to maintain standards of quality and creativity,

But the area is also famous for its wood carvings: angels and saints and devils and skeletons, birds and bugs and fanciful masks all made from balsa wood, the ultra-light wood we used to make model planes from.

Balsa means raft in Spanish. The Balsas River is named for the rafts of balsa logs that used to be main means of transportation in the area before the coming of the roads.

Several families have chosen to paint on amate, bark paper, The making of Amate is an ancient art that persists among the Otomi Indians in the area where the states of Puebla, Hidalgo and Veracruz meet. They use the bark of the mulberry tree (moral) to produce a paper that's almost white. A variety of fig tree (ficus) produces a paper that's a light to mid brown and coarser in texture.

Their paintings depict the timeless cycle of village life in southern Mexico: the tending of crops and animals, the changing of the seasons and the fiestas that mark them, and the brilliance of the landscape and wildlife.

Among the best of these artists is Abraham Mauricio Salazar, who can

often be found selling his work on the Adoquin. Abram's work has been

exhibited in museums in the U.S. and he is the subject of a book and

video. His work stands out because of his vivid sense of color and fine

attention to detail. Simplicio Salavdor is a fixture outside the Hotel

Santa Fe. A carver and an amate painter, his work, if not as technically

fluid as Abraham's, is notable for its bold metaphysical symbolism: lots

of double-faced devils, headless horses and such.

Among the best of these artists is Abraham Mauricio Salazar, who can

often be found selling his work on the Adoquin. Abram's work has been

exhibited in museums in the U.S. and he is the subject of a book and

video. His work stands out because of his vivid sense of color and fine

attention to detail. Simplicio Salavdor is a fixture outside the Hotel

Santa Fe. A carver and an amate painter, his work, if not as technically

fluid as Abraham's, is notable for its bold metaphysical symbolism: lots

of double-faced devils, headless horses and such.

In my experience, you regret what you didn't buy, much more that what you did. Take home one of those knick knacks from among the shelves and it acquires a new dimension, it becomes a true treasure in its alien environment.

This guide is meant to open your eyes to some of these potential treasures. You don't need us to tell you where to buy a t-shirt. But perhaps this overview of the Oaxacan artesian tradition might result in some cherished souvenirs and gifts that will be truly valued.

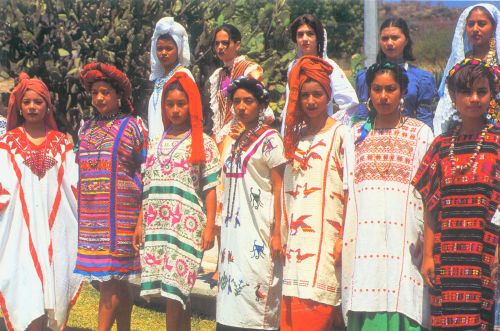

The Zapotec people of Oaxaca have a 2500 year history as master weavers. The links to this ancient tradition are best seen today in the clothing of Indigenous women. Most Indian communities retain a particular style of dress, with variations to distinguish different villages within a region. Elaborately woven and embroidered clothing is worn not just on ceremonial occasions but throughout daily life.

Best known is the huipil, a sleeveless tunic made from three pieces of cloth.

Oaxacan weavers still use cotton and wool yarn dyed with animal based colorants. Cochineal, made from the tiny dactylopius coccus insect that feeds on the nopal cactus, was the most valuable product, after precious metals, shipped by the Spanish to Europe. And no wonder: it takes 70,000 of the insects (only the females are used) to make a pound of dry cochineal. What the Spaniards saw amazed them. The Old World had never seen a dye of such a rich redness and fullness, and so colorfast, so stable and so impervious to change. Cochineal became the most guarded secret of the Spanish Empire.

In the Mixtec villages of the Oaxacan coast, weavers also use cotton dyed with Purpura patula pansa, a species of sea-snail, picked off the rocks of our coastline at low tide during the winter months. When the dyers squeeze or blow on the these molluscs, they give off a foamy secretion which is rubbed onto the cotton.

Although it is initially colorless, contact with the air turns it yellow, green, and ultimately purple, and is highly prized for the typical striped, wraparound skirts of the region.

Also look out for intricately embroidered peasant blouses, many incorporating elaborate beadwork. The woolen rugs and wall hangings from Teotitlan del Valle are also highly prized by visitors and collectors. Also of note are the simple woven-cotton bedspreads, table cloths, place mats and tortilla warmers, all of which can make a splendid gift.

The art of pottery goes back many thousands of years in the New World and demonstrates an astonishing range of creative skills and artistry. While in the West, clay has often been considered somehow inferior to stone or wood as a medium of artistic expression, many archeologists believe that pottery-making was the greatest of all pre-Colombian crafts.

Today Mexico remains a land of potters. Entire villages are engaged in producing ceramic products both decorative and utilitarian. San Bartolo Coyotepec is famous for the black and brilliant sheen of its pottery, a result of overnight firing in a kiln that starves the oxygen from the clay turning the natural red iron oxide to black. Friction polishing brings out the distinctive black metallic luster.

Atzompa is another of the great traditional pottery villages of Oaxaca. Here the distinctive motif is a semi-transparent green glaze using copper oxide over a tan clay.

Ocotlan de Morelos is another important center for the production of ceramics and is home to the famed Aguilar sisters who create colorful and whimsical figurines and scenes: islands populated by mermaids; colorfully garbed market ladies; monkeys and religious icons.

In the villages of San Marcos Tlapazola and Santa María Tavehua the families produce heavy red and orange terracotta ware. Closer to home the ladies of Santa María Magdelana Tiltepec, near Nopala, continue a thousand plus year tradition of producing low-fired, unglazed pottery: cooking pots, vases, simple decorative figurines and the comal, the clay griddles so essential to Oaxacan cooking.

Also available in local gift stores is the highly prized Talavera ceramics from Puebla, multi-colored tiles, plates, bowls and lamps. Wood

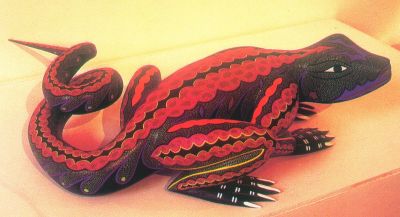

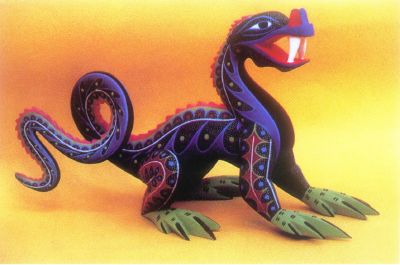

In the 1960's artists in two villages in the Central Valley of Oaxaca, San Martin Tilcajete and Arrazola Xoxocotlán, began carving and painting whimsical and fantastic animals and bizarre other-worldly creatures from copal wood. Copal is a soft, aromatic wood whose sap produces a resin that has been burned in incense braziers since time immemorial.

These alebrijes, as they are called, proved highly popular and today are in demand as souvenirs for visitors and represent one of the state's biggest exports to the international market.

Here on the Oaxaca coast carvers still make animal masks and figurines, especially of jaguars, a creature that has always possessed powerful metaphysical significance. Also common are devil masks and effigies of pink-faced white men. These are based on the ceremonial trappings used in traditional dances for occasions such as the Day of the Dead, Carnaval and Easter Week.

You'll also find carved angels, devils (many, like some of the masks, using real teeth and horns) and the ubiquitous skeleton figures.

These skeleton images are called calaveras or "skulls". And they are seen everywhere, from the political cartoons on the opinion pages of the newspapers to children's toys and games. Far from being solemn or morbid, the Day of the Dead celebrations, with which these symbols are associated, are highly festive in tone. They celebrate the continuity of life and strengthen the links to the past.

Other wooden implements you'll come across are children's toys, especially spinning tops and trucks, combs, spoons, book marks, letter openers, back scratchers and chocolate whisks.

The Mixtecs of Oaxaca were among the most accomplished jewelers of the ancient Americas. The exquisite gold work found in the tombs of Monte Alban is now housed in the Santo Domingo Cultural center in the city of Oaxaca. Reproductions of these magnificent pieces can be found in the Oro de Monte Alban stores, including the one on Puerto Escondido's Adoquín.

Oaxaca is also famed for its fine filigree jewelry. Slender gold wire is formed into elaborate designs and inset with pearls, coral and stone to produce stunning bracelets, earrings, pendants and chains. There's lots of silver to choose from, most all of it from the Guerrero town of Taxco.

Pink and black coral bead jewelry can occasionally be found here, as well as amber from Chiapas and a plethora of fine chiquira beads and shell costume pieces.

(Caveat Emptor: when buying silver, look for the the bell-shaped stamp known as the quinta, alongside it will be a numerical mark, such as ".925", which indicates that this particular piece is at least 92.5% silver. Gold is generally alloyed at 10, 12, 14, 18 and 24-carats. On a 24-carat scale, with 24 representing pure gold, 14-carat gold is essentially 7/12 pure. To check that it's really amber that you're buying, heat it with a lighter and be wary if it exudes a strong plastic smell.)

It probably is not practical to consider taking home tamales or sopes,

more's the pity. But here are some suggestions on how to capture the

taste of Oaxaca to delight your friends and family: The markets offer

rich red and black mole, dry packaged and it doesn't need refrigeration.

Similarly, the delicious mountain grown coffees are easily

transportable. And don't forget about those chile and garlic loaded

peanuts, or sweet peanut and sesame seed bars called palenquetas.

It probably is not practical to consider taking home tamales or sopes,

more's the pity. But here are some suggestions on how to capture the

taste of Oaxaca to delight your friends and family: The markets offer

rich red and black mole, dry packaged and it doesn't need refrigeration.

Similarly, the delicious mountain grown coffees are easily

transportable. And don't forget about those chile and garlic loaded

peanuts, or sweet peanut and sesame seed bars called palenquetas.

Finally, consider two of the most delicious gifts of the New World: Chocolate and Vanilla. Chocolate, that mystic seducer has conquered the world. Oaxacan drinking chocolate is the best in all of Mexico, And vanilla: How ever did it become synonymous with blandness?

This rich silky flavoring is available in markets in bottled

concentrate. If you're really lucky you might come across the actual

bean, which artisans used to twist and weave into animal shapes.